By Federico Zaina

What is this story about?

After 100 days of war, information about the massive destruction of Ukraine’s rich cultural heritage is slowly

coming to the fore. As already experienced during the conflict in Iraq, Syria or Libya, news about damage is chaotic, uncertain or often deliberately manipulated for

propaganda.

In the same way, it is hard to understand whether there is a clear strategy to destroy the Ukrainian cultural identity and tradition or whether the dozens of heritage places destroyed by the Russian army were simply collateral damage of the harsh fights.

This short article aims to show the different positions about the numerous dichotomies emerged in the narration of the events by the media and to highlight some of the key places of Ukrainian culture destroyed or damaged by war.

After 100 days of war, information about the massive destruction of Ukraine’s rich cultural heritage is slowly coming to the fore. As already experienced during the conflict in Iraq, Syria or Libya, news about damage is chaotic, uncertain or often deliberately manipulated for propaganda.

In the same way, it is hard to understand whether there is a clear strategy to destroy the Ukrainian cultural identity and tradition or whether the dozens of heritage places destroyed by the Russian army were simply collateral damage of the harsh fights.

This short article aims to show the different positions about the numerous dichotomies emerged in the narration of the events by the media and to highlight some of the key places of Ukrainian culture destroyed or damaged by war.

Who and why: disentangling the narratives on Ukraine’s heritage destruction?

The conflict that is devastating much of Ukraine has distant roots and is the result of multiple factors. While an in-depth analysis and a relentless update on war developments are provided daily by the media, little attention has been paid to the impact this war is having on the symbols of Ukrainian history.

However, the issue is not easy to address. For example, a strong debate is still revolving around the destruction of museums, theatres or monuments that for numerous journalists and experts is not just collateral damage, but part of a planned strategy to undermine Ukrainian culture and traditions. For example, according to Robert Bevan writing in The Art Newspaper there is no evidence (at least until the end of April) of deliberate destruction of Ukrainian cultural heritage places by the Russian forces.

Instead, quite different is the interpretation of Jade McGlynn and Flona Greenland, published on Foreign Policy in the same week as Bevan’s paper. In their opinion, the current situation must be contextualized in the wider and long-term Russian political strategy of cultural manipulation started with their involvement in the Syrian civil war. Rather coherent (and quite obvious) is the message sent by the Ukrainian authorities. For example, President Zelenksky underlined in many videos the planned destruction of historical monuments and symbols of the Ukrainian culture, as in the case of the Hryhorii Skovoroda Museum in Kharkiv region which was shelled by a rocket on the 7th of May.

In these cases, and with the conflict still ongoing, it is crucial to rely as much as possible on analyses carried out according to scientific methods and as far as possible disjointed to the political propaganda, bearing in mind the difficulty of collecting precise data in similar circumstances.

How many and what: finding the way through data

The importance of relying on analyses carried out with scientific methods is also linked to another big problem, namely the quantification of damage and the identification of the heritage places destroyed.

In the same days of May, for example, UNESCO and Europa Nostra, quoting different sources, reported respectively 100 and 300 cultural heritage places partially or fully destroyed. Later on, on the 3rd of June, the Ukrainian Ministry of Culture and Information Policy, Oleksandr Tkachenko, said that nearly 370 heritage places had been destroyed during the first 100 days of the war. Almost 4 per day…. In this jungle of information, the numerous maps that can be found on the web do not help to unravel the issue. Most of them are inaccurate and in many cases double-checks are strongly recommended.

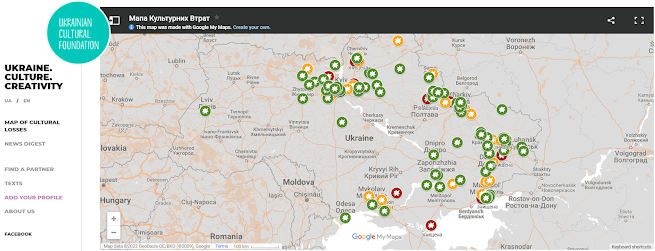

The map I’m proposing here (Fig. 1) is one of the most updated. It has been realized by the Ukrainian Cultural Foundation a state-owned institution coordinated by the Ministry of Culture of Ukraine. Some would certainly argue that this is not an independent source.

However, I can say that besides the numerous double-checks that I personally carried out on other websites, this map was used in a recent publication by the think tank of the European Parliament. The map shows in different colours (red, yellow and green) the places for which it has been confirmed by the government from total destruction to partial damage.

According to the Cultural Heritage Monitoring Lab the majority of heritage buildings destroyed are cemeteries and memorials (58%), followed by churches and other places of worship (30%), museums (5%), monuments and archaeological sites (6%). Many of them received great attention from the media, such as the Donetsk Academic Regional Drama Theatre in Mariupol, or have been repeatedly used by Ukrainian authorities to support their arguments regarding Putin’s plans to erase Ukraine's culture.

Therefore, at the moment, it is difficult to fully comprehend the reasons and the extent of the damage. The most important thing to do is to carry out the most complete and possible documentation of what happens every day. These data should not be used for bombarding people with useless “breaking news” on the TV or the web, but rather to conduct a serious and in-depth scientific analysis once this tragic event will end in the attempt of reaching a conclusion more solid than the ones currently circulating.

Map

of cultural heritage places destroyed in Ukraine since late February (Мапа культурних втрат - Ukraine. Culture. Creativity

uaculture.org accessed 07/06/2022).

Current attempts to protect Ukraine's heritage

Another important

element that received little consideration by the media concerns the legal

framework in which the events that are occurring in Ukraine can be placed.

Is the destruction of

the country's monuments, archaeological sites, churches and libraries by the

Russian army a crime? If so, what tools are available to the Ukrainian and

international authorities to prosecute Russia legally?

It is against

international law to intentionally target cultural heritage and property

in war, according to the 1954 Hague Convention. Since Russia and Ukraine are

among the 133 signatories, the damage to Ukraine’s cultural institutions could

become evidence in a potential war crimes case.

Emerged as a reaction to the horrors of WWII, the 1954 Hague Convention set rules, for the first time, for the protection of cultural property from destruction and looting during armed conflicts. Russia and Ukraine are both parties to the Convention. The text established a “Blue shield” as an easily identifiable sign of immunity attributed to cultural property. The notion of intentional destruction of cultural property as a war crime is further developed in the 2017 UN Security Council Resolution No. 2347 as a reaction to cultural destruction carried out by Islamic State. Therefore, the most important point is to demonstrate intentional destruction. To strengthen the legal position of Ukraine, during the extraordinary meeting organized by UNESCO on 18 March 2022, the Committee for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict envisaged the potential inclusion of some of Ukraine’s cultural heritage property on the International List of Cultural Property under Enhanced Protection, established by the 1999 Second protocol of the Hague convention. Moreover, the committee also granted preliminary financial assistance of 50,000 USD for emergency measures, such as in situ protection and the evacuation of cultural property. Besides UNESCO, an important role was also played by the European Union (EU). On 7 March 2022, the culture ministers of the EU, deeply concerned about the preservation of cultural heritage, unanimously adopted a declaration on the situation in Ukraine.

Furthermore, to strengthen the legal capacity of the EU in the protection of cultural heritage, in June 2021, the European Council recognised the role of cultural heritage for peace and called for its protection during armed conflicts and its integration into the EU toolbox for conflicts and crises. The toolbox is a document describing the institutional framework and the decision-making processes in cases like Ukraine’s war.

Museum

workers carry the sculpture of Ukrainian philosopher Hryhorri Skovoroda

from the destroyed building of the Hryhoriy Skovoroda National Literary

Memorial Museum on May 7 (https://edition.cnn.com/style/article/ukraine-culture-destroyed-skovoroda-museum/index.html).

From astonishment to

action: the role of the international community in rescuing the Ukrainian past

Museum workers carry the sculpture of Ukrainian philosopher Hryhorri Skovoroda from the destroyed building of the Hryhoriy Skovoroda National Literary Memorial Museum on May 7 (https://edition.cnn.com/style/article/ukraine-culture-destroyed-skovoroda-museum/index.html).

The shocking scenario that rapidly developed in the northern and western parts of the country, led numerous countries and international institutions to activate multiple calls to action.

Therefore, while on one side, UNESCO, the European Union as well as many other countries and international bodies condemned the vile destruction of Ukraine’s past and worked to activate the legal processes, on the other side a huge effort has been done to rescue the endangered heritage, to safeguard damaged places and to support the Ukrainian scientific community and heritage experts.

Among others, the Network of European Museum Organisations (NEMO), is providing information about available support from across Europe for Ukrainian museums and their professionals, while a network of 26 Polish museums established the Committee for Aid to Museums of Ukraine, to help secure the country’s collections and provide support. France, the Netherlands and Italy sent materials, and the Nordic Museum in Stockholm has opened a fund to support the National Museum of Ukrainian History in Kyiv. Other groups focused on the digitization of threatened collections. For example, the Europeana platform issued a statement of support for Ukraine and displayed digitised collections of Ukrainian cultural heritage.

The Saving Ukrainian Cultural Heritage Online (SUCHO), a group of more than 1300 librarians, archivists, researchers and programmers, are working together to identify and archive at-risk sites, digital content and data in Ukrainian cultural heritage institutions. The team currently includes academics from a number of university departments internationally. Moreover, numerous foundations like Gerda Henkel and Ernst von Siemens Art Foundation allocated several millions of Euros for scholarships abroad and for humanitarian assistance for Ukrainian researchers and museum curators.

Heritage institutions in Ukraine worked from the very first days of the war to protect heritage places. For example, since early March ICOMOS Ukraine has established a Heritage in Crisis Working Group and The Center to Rescue Ukraine's Cultural Heritage (CRUCH) has been launched in Lviv. On 9 March the CRUCH launched appeals to international organisations, museums, and cultural institutions for help with much-needed equipment and materials. UNESCO Director-General Audrey Azoulay, stressed the importance of marking cultural sites and monuments with the distinctive “Blue Shield” emblem of the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict to avoid deliberate or accidental damages.

Equipment and materials sent by EU countries and stored by the Center to Rescue Ukraine’s Cultural Heritage (Центр порятунку культурної спадщини | Facebook).

We can therefore say that numerous institutions at regional, national and international level have taken action to protect the cultural heritage of Ukraine and support those people who work to protect it. The types of actions implemented range from the effort of single institutions to a coordinated program of rescue activities involving large networks.

Once the conflict has come to an end, it will also be interesting and important to quantify the level of international involvement in Ukraine compared to other countries that have recently suffered similar fates.

Comments

Post a Comment